Events Calendar

View information about NAS meetings and events. Members may view additional information by logging into the website.

Annual Meeting

Watch scientific sessions and events from the 2025 annual meeting and past meetings.

Scientific Meetings

Listen to leading scientists talk about the latest in research.

Frontiers of Science

Frontiers of Science brings together outstanding young scientists to discuss exciting advances and opportunities in a broad range of disciplines.

International Forums

International Forums help scientific leaders forge enduring and productive partnerships.

Public Engagement

Explore the intersection of science and art and engage with science in new and exciting ways.

Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences explores the intersections among the arts, science, medicine, engineering, and popular culture.

Distinctive Voices

Distinctive Voices highlights innovations, discoveries, and emerging issues in an exciting and engaging public forum.

LabX

LabX is a public engagement testbed that boldly experiments with a variety of creative – sometimes even unorthodox – approaches designed to reach diverse audiences.

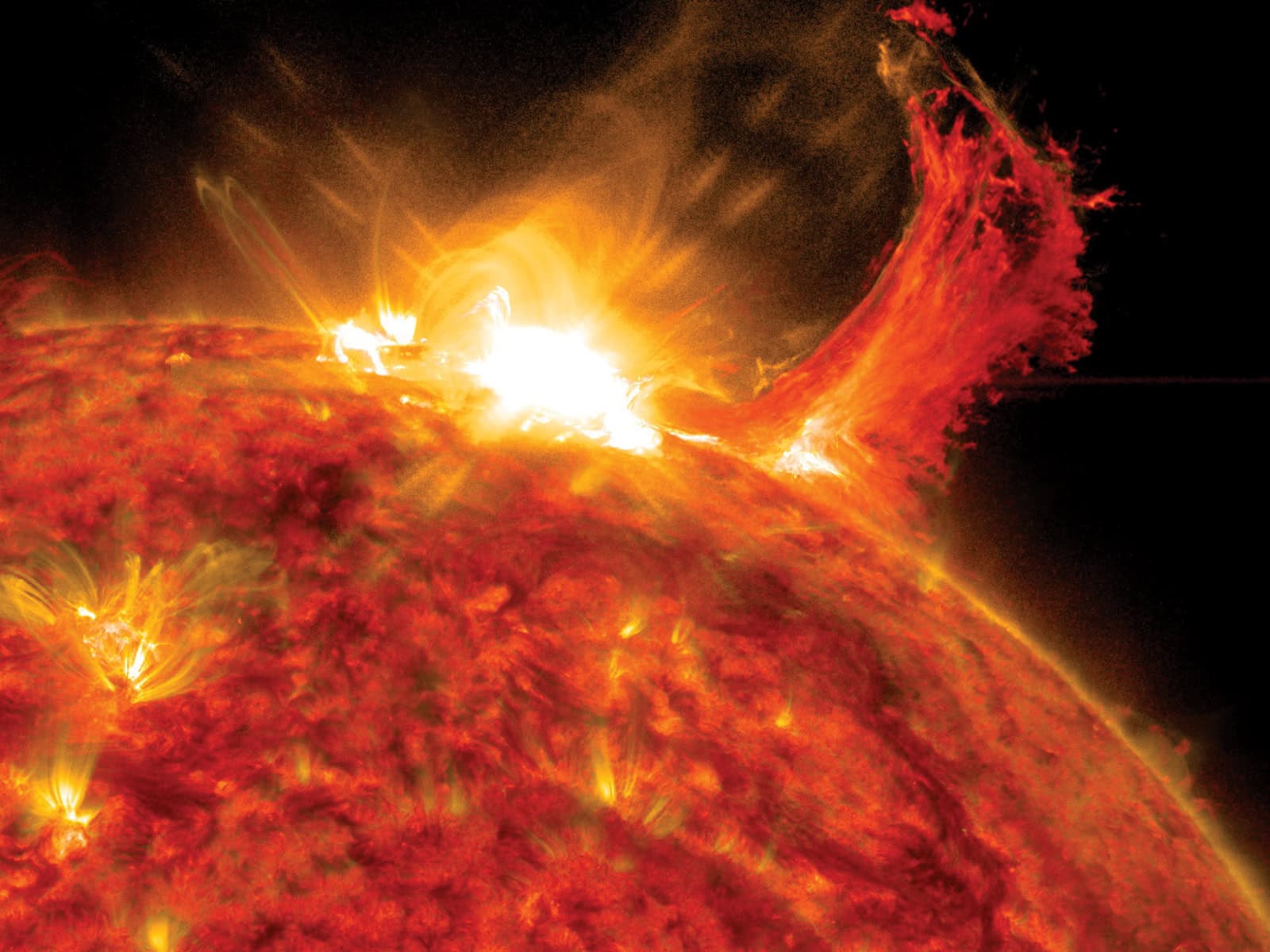

The Science & Entertainment Exchange

The Science & Entertainment Exchange connects entertainment industry professionals with top scientists and engineers to create a synergy between accurate science and engaging storylines in both film and TV programming.

Science & Society

Learn about our special initiatives on national and worldwide issues from human rights to arms control.

National Academies Studies & Reports

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine are the nation's pre-eminent source of high-quality, objective advice on science, engineering, and health matters. Top experts examine and assemble evidence-based findings to address some of society's greatest challenges.

Committee on Human Rights

The Committee on Human Rights serves as a bridge between the human rights and scientific, engineering, and medical communities to advance human welfare and dignity worldwide.

Committee on International Security & Arms Control

The Committee on International Security and Arms Control brings the scientific and technical resources of the National Academies to bear on critical problems of peace and security.

Committee on Science, Engineering, Medicine, and Public Policy

The Committee on Science, Engineering, Medicine, and Public Policy conducts studies on cross-cutting issues in science and technology policy and monitors key developments in U.S. science and technology policy.

Committee on Women in Science, Engineering and Medicine

The Committee on Women in Science, Engineering and Medicine uses scientific evidence to advance gender equity in science, engineering, and medicine.

Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable

The Government-University-Industry Research Roundtable provides a unique forum for dialogue among top government, university, and industry leaders of the national science and technology enterprise.