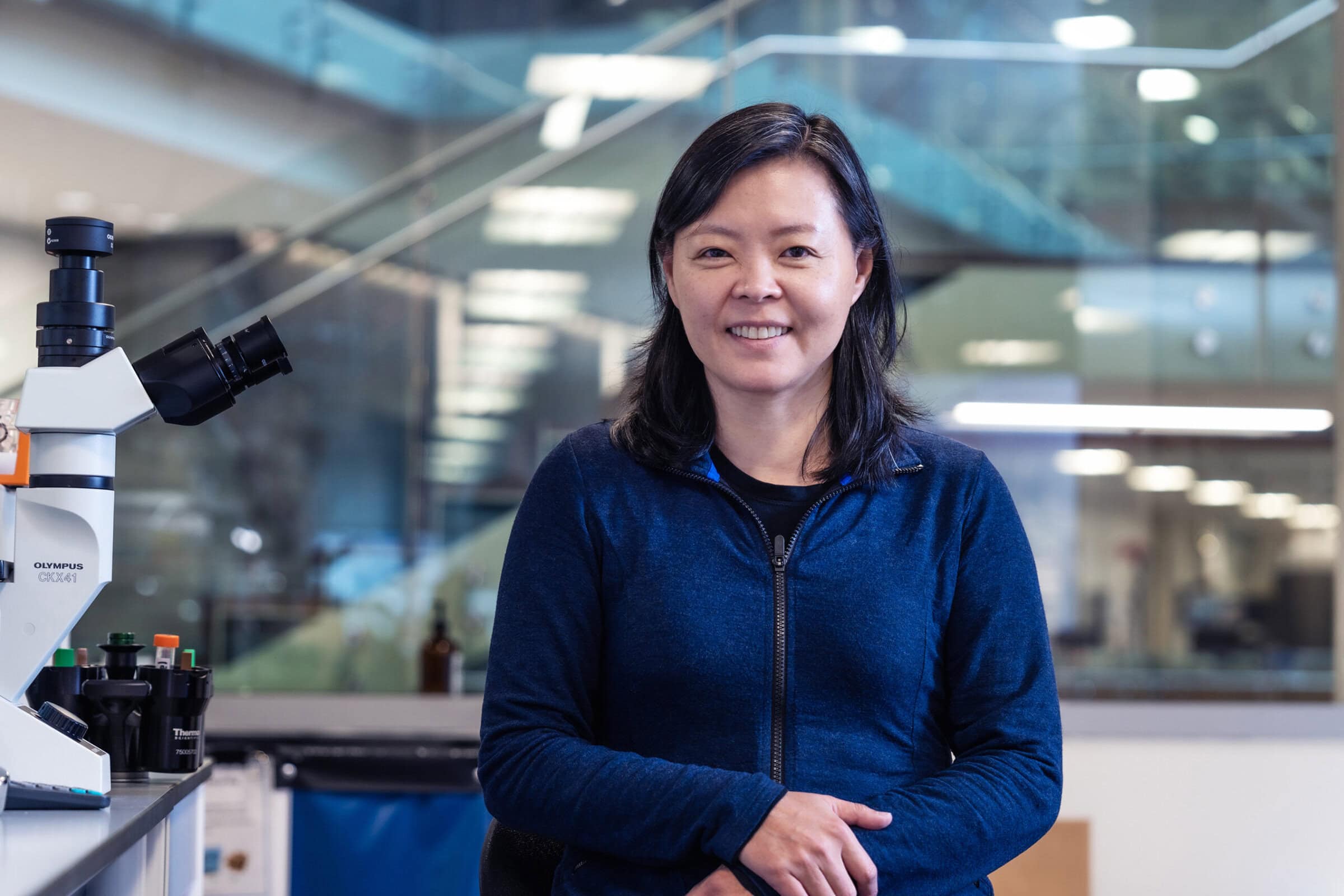

Jonathan Losos, an evolutionary biologist and NAS member elected in 2018, was previously known for his extensive work in herpetology — specifically anoles. His studies of evolutionary radiation of lizards and their interactions with urban environments have had far-reaching influences in the field of evolutionary biology.

In early 2018, the Living Earth Collaborative was launched under the direction of Losos. This working partnership between Washington University, the St. Louis Zoo, and the Missouri Botanical Garden has served as a hub for interdisciplinary and international biodiversity research.

Lynn Werner Marsden Photography

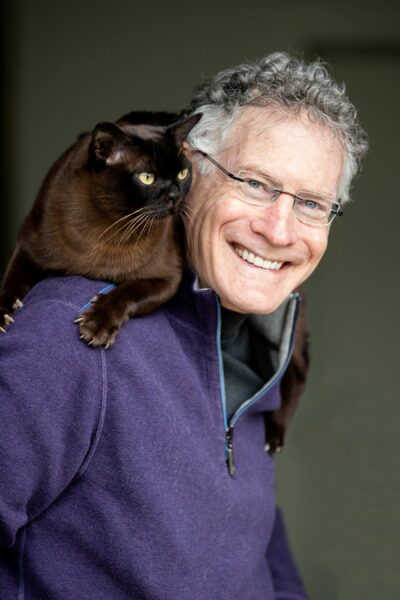

Outside of this work, Losos is also an author, who with his warm and spirited voice, makes complex scientific knowledge accessible to all audiences. His most recent work, The Cat’s Meow: How Cats Evolved from the Savanna to Your Sofa shows a marked change in his research subjects. In honor of International Cat Day on August 8, Losos shares the inspiration for these new studies on feline evolution, and some of its surprises, in a Q&A.

What was your inspiration to switch from studying lizards to studying cats?

It all started when I learned—to my surprise—that there is a lot of great research being conducted on the ecology, behavior, and evolution of the domestic cat, Felis catus. I’m a lifelong cat lover but was under the impression that there were few cat researchers and the work they were doing was mostly focused on management and care issues. Once I realized my mistake, I had the idea to teach a class, initially to first-year students, on the science of cats. The idea was to lure them into taking the course because they love cats, and then sneak in a lot of material on how modern biodiversity scientists study nature using cat research as the vehicle. The course was great fun and very successful—most of the students ended up majoring in some field of science. I, too, became more interested in cat science and decided to write a book for the general public with the same general goal: show readers how we know what we know about the evolution of cats—why they do what they do, and what the future may hold—and how scientists actually gain this knowledge. That book, The Cat’s Meow: How Cats Evolved from the Savanna to Your Sofa, was published last year.

However, during the research for the book—which was quite extensive given the large literature on the subject—something unexpected happened: I became interested in doing cat research myself. From my background as an evolutionary ecologist, I saw unanswered questions and the opportunity to use the methods I’d learned studying lizards to understand cat evolution. So now I’m a cat scientist (or “ailurologist”). My lab and I haven’t stopped doing lizard research, but we’re now taking on cats as well.

When studying the evolution of various animals, what are some common patterns that emerge? Were there any commonalities between the evolution of cats and lizards that surprised you?

Illustration by David Tuss

When comparing the evolution of any two groups of organisms, there are always similarities as well as differences due to the unique aspects of organisms’ biology and the particular events that have shaped their histories. One constant is that natural selection plays a large role in shaping how species adapt to their environment and diversify through time. A common, though not universal, phenomenon is that species occupying similar environments often independently evolve similar adaptive responses. Such “convergent evolution” has been a focus of my research throughout my career and is a topic that we are beginning to study in both feral cat populations adapting to living in new places, and in breeds of domesticated cats.

How has this recent research on cats informed or advanced studies in your field? Has it re-framed your previous work or answered past questions?

It’s too early to say, but we’ve found intriguing evidence of convergent evolution within and between domesticated species, a phenomenon that has received little previous attention.

What are one or two findings from your research that might surprise cat owners?

Again, it’s still early, but it seems like feral cat populations are experiencing natural selection to adapt to the varied conditions they’re experiencing. More generally—though this is a topic we’re just beginning to work on—there is extensive knowledge of the genomics of cats. Because the genome of humans and cats share many similarities, it turns out that research on cat genomics may prove useful for addressing human diseases. Although we’re not going to work on the biomedical aspect, investigating the genomic basis of feline evolutionary adaptation should prove fascinating.

Are there any safe, at-home experiments cat owners could perform that would tell them more about their pets?

Dr. Losos’ cat, Nelson with a tracker

Where to begin? There are all kinds of fascinating behavioral studies one could emulate. One I like has to do with felines’ penchant for sitting in any box they encounter. (This appears true of all members of the Felidae—google “lion” or “tiger” and “box” and see what pops up.) Recently, researchers found that if they used tape to make a square on the floor, their cats would quickly move to sit within it! Additionally, cats are very trainable (they’re very food-motivated!) and trying to train your cat would be an experiment of a sort that might be very useful. Finally, when a cat sees a black silhouette of a cat on a wall, she is initially fooled. Put up a silhouette of a cat with its tail raised high—a sign of friendliness; “I come in peace”—and see if the cat does the same and approaches the silhouette. Be forewarned, however—cats quickly figure out the ruse and stop responding. And one more! There are commercially available cat trackers and kittycams. If your cat goes outside (a fraught question—there are plenty of reasons to keep them indoors all the time), you can study where they go and what they do.

Read more about his work through his NAS member page or his personal website.